written by Hector Chilimani – Program specialist, Ecosystems

Working in communities brings a variety of experiences. If you are leading communities implementing a project or an intervention, there is a lot you learn, from social dynamics, the diversity of the cultures, values from one village to the next, the stories associated with some historical places and artifacts of attraction that you come across while navigating around those communities. It is always a privilege to work with rural communities, at least that is my experience for the past 9 years of community work across health, agriculture, microfinance and development across Malawi’s rural communities, which proportionately has over 80% of the total population.

Of great inspiration has been the potential of communities to bring out their home grown solutions, addressing their problems while we facilitate platforms that motivate shared learnings on how previous experiences can help address current problems. Context matters, it always does. The novel Coronavirus (Covid-19) has not left any corner of the globe, at least by the spread of the news (and related myths). Though Malawi has registered few cases of Covid-19 (4 deaths at the time of writing this blog) the tension, anxiety and curiosity is being felt across the country, no matter the class, race, sex or religion. Everyone listens to all manner of media outlets (mass, social and fringe), is vulnerable to the same rumor/fear mongering and, in many cases, have no way of verifying the authenticity of this misinformation, masquerading as messages. This is especially hard for rural-based populations in developing countries like Malawi whereby it is highly likely the nearest health facility is a few kilometers away meaning access to a healthcare provider is not guaranteed. Further to this, local governments are either over-stretched or under-resourced (or usually both) to mount an effective and comprehensive response – this is where civil society organizations, like BASEflow, come in; we both fill a gap and complement existing efforts to ensure communities have the correct information to effect individual-level responses.

We always try to align to the needs and abilities of the communities we work with, and this approach has helped us to leverage these community experiences and abilities in the implementation of the Mleza Irrigation and Fish Farm Scheme, an ecosystems project that is working to maximize groundwater for sustainable agriculture, collaboratively supported by University of Strathclyde, the Scottish Government’s Climate Justice and Innovation Fund(CJIF) and co-financed by Irish Aid, in the village of Jordani in Blantyre district. Knowing the global awareness around COVID-19, we knew that news of the outbreak, could not be ignored and would filter into community conversations on our routine supervisory calls, likely to arouse superstitions and anxieties.

COVID-19 has brought more questions, but has also reminded us of somethings we have neglected or taken for granted for many years. Though not part of existing programming, we saw this as an opportunity to re-look at those practices and see how they can be promoted and embraced within our existing work with Jordani, knowing how critical they are as part of general disease prevention.

As such, on 27 March 2020, using our resources from BASEflow services, we organized a small gathering of 5 local leaders, village development committee members, government extension workers from health, agriculture, community development, forestry and water departments to discuss and share information regarding COVID-19, what it is, what it isn’t and what they could do about it under the agenda “Understanding and Preparedness for COVID-19”. On this day, though considered custom at the start and end of any gathering, handshakes were not entertained during the gathering, emphasizing that this was a global as well as local prevention measure to minimize the spread of the virus. There was a mix of laughter and silence when someone reminded us to: “make sure we are not more than 120”, followed by a correction from another participant, “Actually we should be less than a 100 of us, and we are 34 here”.

People had already heard something about the outbreak before our visit. What a great start to the day!

We took time explaining and discussing why handshakes should be avoided, and rehearsing the alternative handshakes. Waves, winks, and many other examples.

And from the group, rose a question: But how can we avoid touching our faces? We exhaustively discussed why this was really important in breaking the virus’ spread and why thoroughness and consistency in washing hands with soap was really helpful, ensuring that others are doing the same.

A follow-up question came, “Does it mean we are no longer going to greet each other with a handshake?”

Our simple response was that: “Not really, but after all is said and done about COVID19, our perception of a handshake will definitely change”.

I can only imagine the mindset shift the community must have been experiencing to start seeing a handshake, a gesture of genuine love, peace and openness, as a potential weapon of destruction.

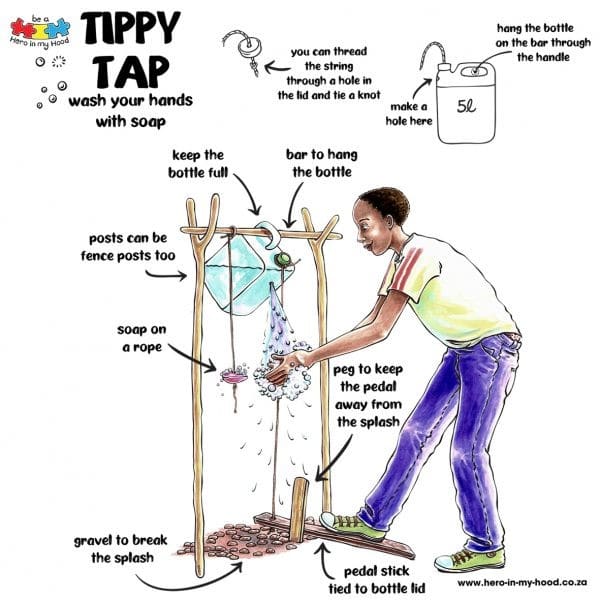

Following the information sharing, it was time for some hands-on work around handwashing: how they usually wash their hands, what resources they use and what would be the easiest technology to be introduced in their homes. A resounding chorus, as if rehearsed, from the gathering was “Mponda Giya” (vernacular for the Tippy Tap (see picture 1)), a basic handwashing technology/station made using plastic bottles, sticks and a string.

Picture 1: Tippy Tap Handwashing Station

They narrated that they had previously installed these as a way of responding to hygiene related diseases. It was at this point that we learn that these no longer existed, but they could easily develop them in their homes, all they needed was motivation. Having earlier discussed COVID-19, and how important the practice of handwashing is, we agreed to conduct a demonstration right there and then, and leave an exemplar that the rest of the community could emulate/replicate; all they needed was a 5-litre bottle which we got from the car. They then organized themselves, got a knife, a pale with water, and plucked branches from a tree nearby and got to work. And right before our eyes, we watched as the tippy tap came to life. (see picture 2 below).

Picture 2: Demonstration Handwashing using a newly constructed Tippy Tap

Finally, the participants challenged us to have a door-to-door visit during the next routine supervisory field visit to assess the level of household adoption. This, though simple, was a quick win and a step forward.

We may not have figured out how to practice social distancing in the rural homes that are often small spaces with extended families; however, we have started somewhere to providing the community with the necessary knowledge and tools to protect themselves against Covid-19.